The Dark Side of Franchises

- October 20th, 2014

- Posted in Opinion/Analysis

- Write comment

I’ve talked a lot here about franchises, the advantages that they offer to fans and the reasons they are so appealing to the studios. But the reality of the franchise phenomenon has a lot of downsides, too, and as the size of moviegoing audiences shrinks and the number of live TV viewers dwindles, these downsides have only become more prevalent. Today, let’s delve into the dark side of franchises, and explore why giant franchises aren’t always a good thing.

I’ve talked a lot here about franchises, the advantages that they offer to fans and the reasons they are so appealing to the studios. But the reality of the franchise phenomenon has a lot of downsides, too, and as the size of moviegoing audiences shrinks and the number of live TV viewers dwindles, these downsides have only become more prevalent. Today, let’s delve into the dark side of franchises, and explore why giant franchises aren’t always a good thing.

Usually, I take the approach that more is better–more shows and more films, all connected, make for a bigger and more interesting world in which the story takes place. We get to examine it far more thoroughly, and potentially in so many different ways, that otherwise would have been impossible. This is only possible, however, due to one simple fact: the show or film belongs to the studio corporation, not the filmmaker or original creator. Hollywood already has a huge power advantage in negotiations with aspiring writers and directors; after all, if you won’t play ball, there are a thousand others in LA alone, just waiting for this chance. You’d be a fool not to take it, right?

What that really means is handing over the rights to almost everything in order to see it made. Gene Roddenberry created Star Trek, but his estate doesn’t own it; Paramount does. Gene’s son, Rod, doesn’t get a say in what happens to Kirk and company. At least, not in the same way that, say, the estate of Raymond Chandler does about Philip Marlowe (hence TNG’s pastiche of the character in Dixon Hill, as opposed to using the original like with Sherlock Holmes). To a certain degree, this makes sense; films and television are far, far more expensive than a book to produce, and are as much the creation of the actors, producers, and other writers as they are of the original creator. This is one of the big reasons behind George Lucas’s decision to fund Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi with his own money; that way, no studio could redefine the contract to take away the few rights he’d managed to retain (and made the best of) again.

So when these properties belong to corporations, the suits approach the issue in the only way they know how: money. How best can they leverage this film/television property in order to make a profit? If the show’s going strong, make a spinoff. If the last installment wasn’t well received, do a reboot. Actors don’t want to cooperate? Recast them. Whatever it takes to keep the intellectual property (IP) in the public eye and enable the sale of licensing and merchandising to whatever they can. As the years have gone on, and more and more people have resorted to venues like Netflix, or before that, video rental, to see movies, the Hollywood studios became more and more dependent on the idea of blockbusters, huge, expensive films that run on spectacle and (theoretically) are sure to draw in a crowd. But when you’re investing so much money into a film and your only real goal is profit, you want to do everything in your power to make it succeed. And leveraging existing properties by using those well-known names as the basis for your blockbuster is one sure-fire way to get at least the old fans back in.

Lines and lines of identical products, devoid of uniqueness or creativity, manufactured in the image of another.

What has started to happen is that when studios come across spec scripts that they like, if they’re even vaguely similar to an IP that they already own, they’ll ask for a rewrite on the script that makes it fit with the established property. This is what happened with the infamous I, Robot film, for example. The original script was called Hardwired and started out as a murder mystery featuring robots. Fox, already in possession of the rights to Asimov’s works, reworked the film into a big-budget blockbuster with just enough connections to Asimov’s works to justify changing the title. Never mind that the film’s central premise of a robot uprising goes completely against Asimov’s descriptions of how the robots work and function; some executive who’d never read Asimov saw robots and stuck them together. Now it now had a recognizable name that could draw crowds in. Would Hardwired have been a good film on its own? Impossible to say; the end result is so different than how it started that we can’t use that to judge. If it hadn’t come along, would there have been a different, more faithful I, Robot movie? Maybe. In the end, the studio’s desires to make a quick buck ruined the original project and angered fans of Asimov’s work, but they made their money and that’s what matters.

Original scripts aren’t just co-opted to become new installments of old IPs, however. The studios’ growing reliance on so-called “tent-pole” blockbusters, which are supposed to more or less singlehandedly support the studio for the year, means that they’re very, very hesitant to invest in unproven properties. Why risk spending hundreds of millions of dollars on an original film, when you can just make another Transformers/Batman/James Bond/etc.? Those are known quantities, with proven track records and mountains of evidence to show that they make money. If not a reboot, or a remake, or a sequel, then an adaptation of something else that already has a known audience (e.g. Hunger Games). That leaves very little room for original works. The only reason that James Cameron is able to make an original film in Avatar is that he had colossal successes like Titanic and Terminator behind him, and even then he had to promise Fox that he’d sacrifice his director’s fee if the movie failed.

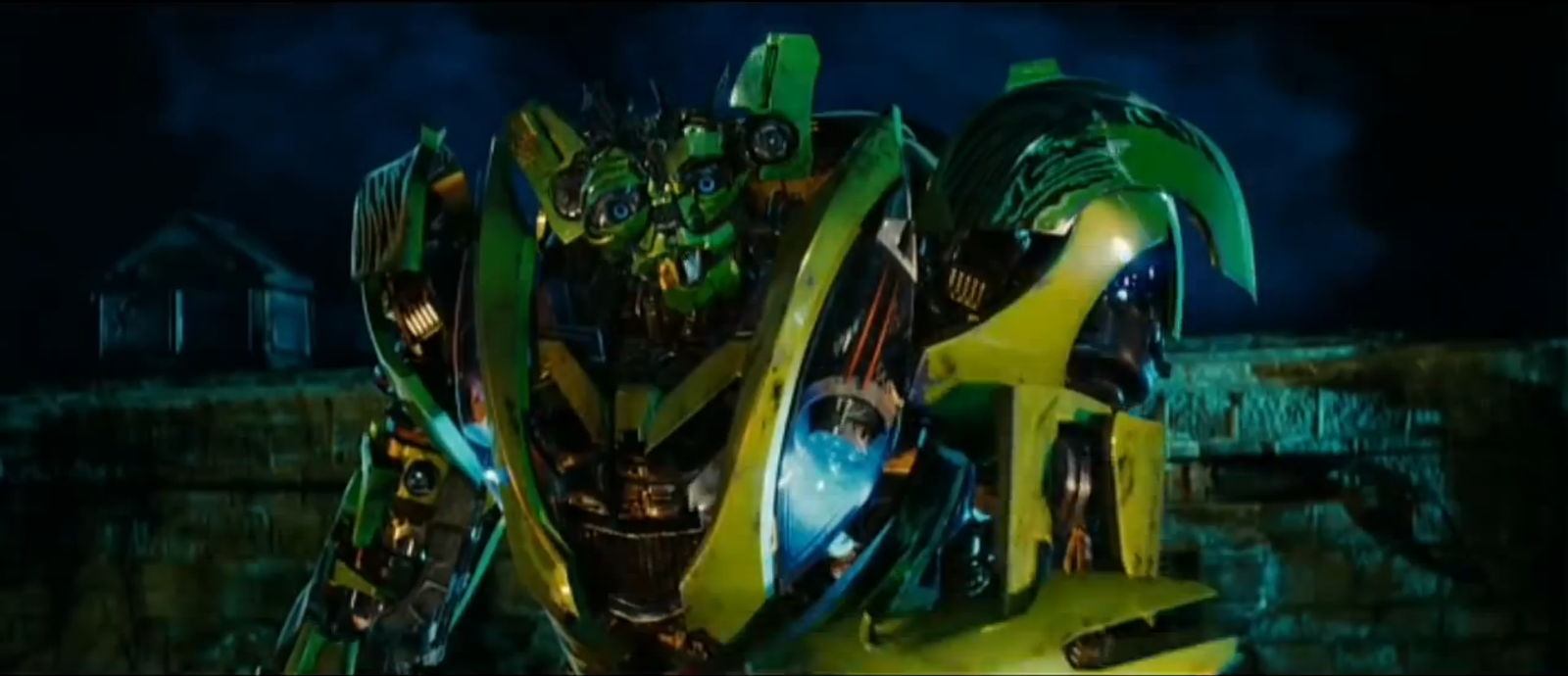

And since these big budget tent-poles have so much riding on their success, it means that the studio wants a big say in how they’re made. Films that get made only because they have big stars attached who are definite box office draws, selecting only directors that will work the way the studio wants them to work. They’ll get pushed out early, start shooting without a finished script (Transformers 2). Sure, after a degree of success some directors can get a little creative freedom, like with Cameron or Christopher Nolan, but that’s far from certain. And with the recent move towards these shared cinematic universes, that takes even more creative freedom away from the director. While I love the Marvel films, they’re also one of the guiltiest parties when it comes to taking away directorial freedom. There’s a certain atmosphere expected of a Marvel film, and they want that consistent. In some ways, it’s almost like the old school Studio Era in the early 20th century. Most recently, Marvel had big name director Edgar Wright leave the Ant Man project, which he had been pushing for since even before Iron Man, because the way they wanted the movie to be was incompatible with his vision of it. And he’s far from the only director that has had problems dealing with Marvel’s strict oversight. Clearly, it’s working for them, to an extent; the Marvel Cinematic Universe is still an amazing and unprecedented thing, and practically prints money with how popular it is. But from an artistic perspective, it’s certainly troubling.

In the end, the situation that we’ve found ourselves in is a complex one. It has its pros and cons, for both fan and filmmaker alike, and whether you personally feel it’s a good or a bad thing is going to depend very heavily on where you lie on the spectrum. I certainly have complicated feelings about it myself; as someone who would love to break into the industry, it’s worrisome to watch the slate of studio-backed movies shrink down to a handful of established properties each year, although they do all have their award-seeking specialty divisions that tend to put out higher-brow content. On the other hand, it’s opened up a lot of space for indie films, which are a far more likely place for someone to get their start these days, and more fun, too. And as a fan, these curated shared universes are practically a dream come true. If you’d told me 10 years ago that Captain America would now rank among my favorite movie heroes, I’d have laughed in your face. And yet here we are, with Captain America 2 one of the most praised films this year. So I’ll be cautiously optimistic, for now, and hope that this system doesn’t end up collapsing in on itself under its own weight.

No comments yet.